The Golden Age of SaaS

Many, many, many of us got stuck. We built the company we were “funded” to build, and now we’re told our company is un-fundable.

“Growth!” they said. “We got your back!” they said. “There’s more money where that came from,” they said.

So we hired, we built, we launched. We expanded, we sold, we committed. And COVID turned out to be a gift. With remote-working companies needing more software, SaaS went on a growth tear in 2020 and 2021—even faster than before. If there was ever a time to grow and grab market share it was then. VC and PE funds couldn’t deploy funds fast enough, we couldn’t hire fast enough, and the one thing that kept it all rolling was growth. Growth, growth, growth.

“Triple, triple, double, double,” they said. “Rule of 40,” they said.

And of course, since we knew how to hire people and build go-to-market teams, we did just that.

Return to Earth

And then in 2022 it all came crashing down. Growth was no longer sufficient for investors. The new round of funding that was certain 6 months ago based on “growth at all costs” was now inaccessible. The IPO market froze up solid. And public market investors pulled back on hyper-growth as a primary thesis.

This left many SaaS companies stranded, from Series B all the way through publicly-traded. If this was you too, I’m sorry. That was a rough, rough go.

Our first order of business was to stop the bleeding. This is why we saw so many layoffs—we simply couldn’t carry the same cost structures we did previously. We had to get our burn rate down to a level (either low or negative) that would allow us to survive at least a couple years without outside funding.

With the bleeding stopped, we had to dig into our unit economics: LTV:CAC, Magic Number, CAC Payback… any of these would do. Triple-triple, double-double doesn’t contemplate cost at all. And “Rule of 40” allows us to outgrow our costs—we could even have negative profit, as long as it was fueling hyper-growth. But once we dug into these unit economics metrics—LTV:CAC or Magic Number or CAC Payback—there was nowhere to hide. Unit economics holds us to account for every dollar we spend on GTM. It requires our GTM to be profitable in and of itself. Since we had let costs run away with us, and since growth was all but dried up, we were stuck. We may have been able to attain “growth at all cost,” but sustainable growth was elusive.

Did we cut into bone? In addition to cutting non-performing quota carriers, did we have to cut enablement? Ops? Product? Whatever we did, it was a survival tactic. But now we have to architect a plan going forward that produces reliable and sustainable growth. (More on the causes and effects of the SaaS Crash here: The Sweet Spot in the Eye of the Storm.)

2024

As we build our 2024 revenue plan, it behooves us to think fundamentally about growth. To make unit economics work, we need each dollar we spend in sales and marketing to produce at least 3 dollars in expected LTV (lifetime value).

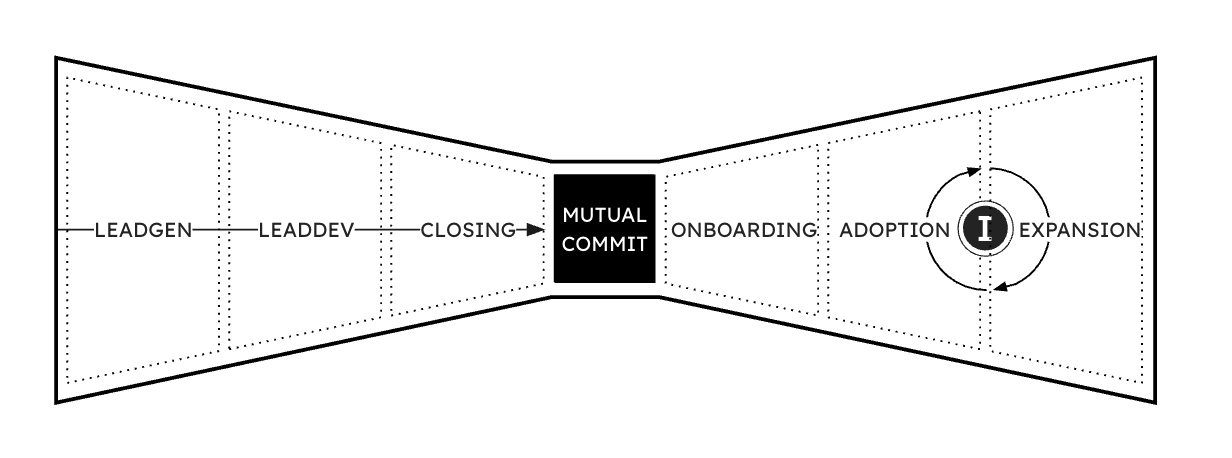

Many companies are looking at how to scale their human-led GTM motions and how to get more efficiency and more sustainable growth along the way. This means defining processes and playbooks, working on skills, and implementing measurement for the core activities across the bowtie.

The more consistent and reliable our human-led motions, the more growth we can achieve via the compound effects of many small improvements (see Law of Marginal Gains).

Getting a methodology to “stick” in a human-led system is an entire art unto itself. (More on this here: How to Make a Go-to-market Methodology Stick.)

How much should we spend on this? Whatever it takes. Our survival depends on it. That doesn’t mean doing huge projects, per se. It means we need to stick to this until we get the efficiency we are looking for. Design, activate, operate. Measure and optimize. Get it right or go out of business.

Disrupting Yourself

Getting back to basics and building an efficient and sustainable human-led GTM is a necessary step. If you have not done this, plan for it in 2024 urgently. The alternative is to become a “zombie company,” a condition that takes years to play out, as SaaS companies die slowly. Fix your human-led GTM!

But in most markets, building an efficient and sustainable human-led GTM will not be sufficient in the long run. You may have a competitor right now who is employing product-led tactics to automate portions of their GTM. This may seem innocuous (e.g. “they’re going after the bottom of the market; I’m going after enterprise.”), but it is not innocuous—quite the opposite. Their success in product-led GTM portends disaster if you don’t get in front of it now. (More on this here: Is PLG Right for Me?)

Ask yourself:

If you were to start a new company today in your space, knowing what you already know about your customers, your competition, and the features and processes that create Impact, what might you do differently?

If you had the luxury of raising money today to start a brand new company to compete with your own, with what subset of features would you begin ?

If you had limited money to hire and and onboard people, how would you allocate investments across product and GTM?

If a competitor were to attack your current position, against which tactic would it be most difficult for your current company to defend?

Chances are, you know exactly how to beat yourself. You know which customers you would like to “fire”—the ones controlling your roadmap with unreasonable demands. You know which product features you wish you had never built, but now you can’t let them go. You know which features you would build next, if you could get to them.

If you know it, your competition also knows it. They know how to beat you, and they are working on it right now.

Now is the time—when financial markets are resetting—to make structural adjustments. Fire the customer(s) you know are draining you. (More on this here: Angel Customers & Demon Customers.) Focus on core customers and core features. Get PMF (product-market fit) right in the way a new startup would have to get it right. Measure it. Fine tune it. Allocate investment money in product and GTM the way it makes sense to you. If you are vulnerable to attack via a specific competitive tactic against which you “can’t” defend, because that’s now how your business was built, reconsider. Here are some examples:

Your competitor gives away API calls, but it’s a core monetization lever in your product. They are gaining ground on you, and you’ve been hesitant to switch.

Your competitor leverages a “good enough” AI integration for free, while you use a more sophisticated one that costs per token. This allows your competitor to give away their AI functionality to gain market share against you.

Your competitor offers pre-built integrations to adjacent platforms as a core feature of the product. Since these integrations are limited, your approach has been to charge for custom integrations that cost more but are more feature-rich.

Your competitor’s reporting is slick. Yours is more powerful, but theirs is slick and easy to use. How would / could you revert to simpler reporting?

The Big One: PLGTM

Of all the tactics a competitor might use to unseat you, the most dangerous tactic is PLG. Why? I’ll lay it out in a dramatically hyperbolic parable. Adjust to your situation as you see fit.

***

ZombieCo vs. Gnat, Inc.

There once was a regional SaaS darling named ZombieCo. They had attracted all the right investment and all the right talent. They were widely heralded as the “next big thing.” Their CEO accepted awards on their behalf, they made many “top-10 lists,” and their customer events were love fests.

Since money flowed freely to fund growth, ZombieCo raised and spent to fuel hyper-growth. They hired sales teams and sales managers to sell the product. They hired customer success teams and managers to implement and support the product. And the growth kept on coming. Until it didn’t.

When growth stopped, money also stopped. Investors were no longer interested in “growth at all costs,” and they certainly were not interested in low-and-expensive growth. ZombieCo could suddenly not afford its payroll. Local press was shocked to report layoffs at their beloved company.

Layoff decisions were hard to make. “Management have the highest salaries, but if we lay them off, who will manage the teams? On the other hand, we would have to lay off 2-3 salespeople or Customer Success people for each member of management we keep. What about engineers—could we cut there?” What to do? ZombieCo did the only thing they could do—they kept a skeleton crew, with a minimum amount of management to keep each department functioning. Then they hunkered down to wait out the SaaS apocalypse. ZombieCo’s investors did not have helpful suggestions. “This is going to be tough,” they said, followed by, “We have an upcoming annual meeting. I’d like to invite you to present to our LPs. It is at a very nice resort, and I know you can use a break. Your peers will be there too.” Except for funding their own events, investor hands and wallets remained in their pockets.

Meanwhile, in a spare bedroom of a small house in the suburbs, a startup competitor was born. Gnat, Inc. did not have all the right investment—they had bootstrapped. Since they couldn’t afford salespeople, they built a simple product that could sell itself. They introduced the product to a few startup incubators and watched and learned while new users struggled to understand or use features. Each time confusion surfaced, Team Gnat dove in to clarify the user experience by making features more intuitive. Gnat watched ZombieCo carefully. They carefully selected the Zombie features their customers were also demanding and built those into the Gnat product, testing for usability as they went.

Gnat was aware of Zombie, but Zombie paid no attention to Gnat. After all, their product was cheap, their customers were small, and their feature set was limited. Gnat was on no top-10 lists, were wining no awards, and were not attending any VC LP dinners. Even when growth dried up, Gnat seemed to fly under the radar. No layoffs to announce, no drama, almost no footprint in the industry whatsoever—except among the small and medium-sized businesses who seemed to prefer Gnat’s product and price point over Zombie’s.

Since Gnat was bootstrapped and couldn’t pay salespeople or CS people, they had to make their product self-service. Customers could find, adopt, and succeed with the Gnat product on their own. The only human involvement was a support chat, where Gnat’s CEO would personally help customers who got stuck or confused. Lessons learned on this chat were immediately incorporated into the product to make it easier for the next customer to understand. With no GTM payroll, each “sale” of the product was profitable. Profits from new customers were re-invested in the product’s user experience—making it even easier to discover and adopt. Sometimes these profits were also invested in new feature experiments—experimenting to see if the new feature could be made easy enough to be discovered and adopted via self service.

As ZombieCo continued to pay managers and salespeople to not hit quota, growth stalled. CS people scrambled to convince existing customers to not downsize their contracts. They used discounts, multi-year incentives, and free months, but to no avail. ZombieCo’s shrinking contract base and slowing rate of new customer acquisition resulted in flat growth, and Zombie was barely able to meet payroll. Conversations about future layoffs loomed.

Given their relative cost structures in GTM, ZombieCo continued to lose money while Gnat made money and re-invested it. Slowly, as Gnat’s feature set expanded, they made their way upmarket and won a select few small enterprise customers. They treated enterprise customers as experiments also. Rather than selling large or multi-year contracts, Gnat encouraged small, departmental contracts that expired in one year. Each time they landed an enterprise contract, they carefully tuned the product experience to make sure they were not introducing a dependency on human assistance if it wasn’t absolutely necessary. Gnat’s product continued to be the easiest-to-use product in the market, and it began replacing Zombie in key accounts.

Five years passed. Zombie flirted with bankruptcy and was eventually sold for parts. They had not been able to exit their death spiral, caused by salaries paid to generate growth that did not materialize. Gnat, meanwhile, began appearing on top-10 lists. The previously unknown startup was now at the top of their game, with the frugal founder-CEO worried about how to maintain agility even as they assumed market leadership.

***

The above is a parable, and the names have been changed to protect the innocent. But if you recognize any of your own situation, now is the time to sit up and take notice, before it is too late.

The hero of this story is not Gnat, Inc. No, this story’s heroes are the core principles of Product-led GTM. Applied systematically, these principles could have helped anyone. Even ZombieCo could have avoided their ignominious death, had they stayed true to Product-led principles… specifically in their go-to-market motions.

Why?

Because money spent on human-powered GTM steps that could be automated is wasted money. You will never get that money back. It is not being invested—it is being wasted. Assuming the same GTM task could have been performed for zero marginal cost by the product, your choice to pay a human to do that task is a drain on your resources.

Consider the commercial farmer who chooses to hire laborers to turn the soil by hand rather than using a tractor.

Consider the manufacturer who chooses hand assembly rather than machine-assisted assembly.

Consider the publisher who has each copy of a book hand-lettered by a scribe instead of using a printing press.

No one would make these decisions. Why? Because spending money on inefficient production is wasteful, and the company that so chooses goes out of business. Due to long-standing relationships or multi-year contracts, some inefficient companies can stay in business for a few years as a Zombie Company, but eventually they will be replaced by more efficient successors. (For more on Product-led GTM, see Is PLG Right for Me?)

How to Avoid Zombiehood

Do you like taking medicine? Going to the gym? Eating vegetables?

No?

What about firing friends? Abandoning long-standing customers? Canceling products?

Also not?

Well… buckle in for this next section; it’s going to get uncomfortable.

The only path to thriving in SaaS is unit economics.

There, I said it. The SaaS equivalent of vegetables is unit economics. Get them working for you, and you will thrive. Ignore them at your peril. The Golden Age of SaaS was like being a teenager—you could eat whatever you wanted and you’d still look and feel good. That era is over. SaaS is no longer a teenager.

Unit economics work like this:

You sell a product. After paying for COGS (cost of goods sold), as well as the variable marketing and sales expenses incurred in securing that sale, you generate a margin. We call this the Contribution Margin.

You pay salaries (the major fixed expense category for most SaaS companies). These might be headquarters personnel (CEO, CFO, HR, etc), they might be product personnel (product managers, designers, engineers), or they might be sales and marketing personnel (including customer success, assuming you don’t account for them in your Cost of Goods Sold). Let’s bundle all these salaries with any other fixed expenses that don’t vary with sales (e.g. rent, software licenses, etc) and call them Fixed Expenses.

Now we determine how many product sales (each of which generates a Contribution Margin) are needed to pay back our Fixed Expenses. We call this our Breakeven Point.

“Wait a minute!” you say, “SaaS has recurring revenue, so we get profit long beyond the initial sale.”

Yes, that is true. So for our purposes, call Contribution Margin the sum total of expected cash flows from that sale, discounted for risk and cost of capital. Regardless, the principle holds:

The only path to thriving in SaaS is unit economics.

It was once true that we could lose a little money on each sale, as long as we were generating growth (in other words, generate negative Contribution Margin). Financial markets would “fund” that loss, because they were more interested in growth, which they could parlay into high returns (as long as they could sell to the next investor at an attractive valuation). Fundamental underlying economics did not support those valuations, but since they existed, investors took advantage.

But that was then, and this is now. We are no longer teenagers, and we must watch what we eat. That means making sure our contribution margins are healthy.

SaaS has a few standard ways of summing up unit economics into clever measures that account for expenses and returns: LTV:CAC, Magic Number and CAC Payback are the most prominent. For reasons beyond the scope of this paper, I prefer CAC Payback—it leaves nowhere to hide. The rule of thumb is that the net revenue generated from the sale of a product pays back CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) within 5-14 months, depending on segment. CAC is a stringent calculation, and it is calculated by dividing all sales and marketing expenses (salaries, commissions, fixed expenses, variable expenses) by all new sales (weighted or unweighted).

Until we have paid back CAC, we have generated zero Contribution Margin. Since we load all sales expense into CAC (including salaries), our burden of carrying unproductive salespeople is felt acutely. If we have a CAC payback beyond one year, then our first year’s contract and payment does not make us “whole.” Not only have we not paid back our sales and marketing costs, we have also not contributed to funding product and HQ expenses. In this situation, every new deal drains resources for at least a year.

If you don’t understand your unit economics in detail, chances are you are at high risk of Zombiehood. It’s easy to point to growth metrics and declare victory. Or in the absence of growth, it’s easy to point to retention metrics and say, “at least we’re holding steady—these customers are paying the bills.” But SaaS metrics like CAC Payback exist for a reason. They help management avoid the traps of “vanity metrics,” and they tell the truth.

Chances are, if growth has stalled, your unit economics do not look good. Examine them carefully by product and by segment. Be honest about how you allocate sales and marketing costs. In this situation it is likely your enterprise GTM is the least economic part of the business. High salaries for unproductive salespeople, combined with the support structure around most enterprise teams, can get exposed quickly in a unit-economics analysis of a stalled-growth company.

So what do we do in this situation? The same thing we would do as a young company with no funding--we have no choice. We kill the things that are not profitable and keep only what is working. Here’s a checklist that roughly outlines options in order of consideration:

Is the CAC payback of your enterprise new sales operation greater than 14 months? If so, consider dismantling the entire enterprise operation. Cut to the bone. All salespeople, sales engineers, enablement, and marketing that support enterprise new customer sales.

Once you’ve dismantled your enterprise new sales operation, you will notice large enterprise customers counting on you for outstanding roadmap commitments. These customers no longer have salespeople taking care of them. Fire these customers also. Let them know you will not be following through on commitments, and refund money as necessary.

Do you have any products or geographies where CAC Payback is greater than 14 months? If so, shut down these products and geographies. Pay severances, offload leases, and be aggressive about product sunset schedules.

Examine the rest of your new business operation—your mid-market and SMB GTM motions. In these segments you really should have CAC payback of < 1 year. If you’re not there, why not? Can you lower CAC by making your GTM more efficient? This is typically done by implementing playbooks and processes (commonly called a GTM Methodology). You need to either fix these GTMs or eliminate them. You may end up with smaller teams here, but hopefully highly efficient ones.

What is left after all this surgery?

A clear view of what is working in your business

A focused team

A product team with renewed confidence—they were watching you carry unproductive and expensive salespeople. Now they see you made some hard decisions, and they have more confidence in you and the company’s future

A Customer Success team responsible for taking care of core customers on core products only

A company comprised of only profitable businesses

Unit economics working in your favor

Now that each part of your business is profitable, you can afford to look for ways to automate GTM and streamline the ease of use for your products. Each investment here will work to improve unit economics even more.

Will you ever build back your enterprise business? Of course you will. But you will do it methodically, like Gnat, Inc. did in the above parable. You will look for departmental adoption (not company-wide adoption). You will treat each new type of customer as an experiment, and you will iterate to seamless success before you begin replicating it.

This is the path trodden by living SaaS companies, and these are the necessary adjustments to avoid Zombiehood. If your analysis shows that surgery is required, here’s wishing you a healthy dose of courage. But the pain of executing a focused get-well plan is far less than the pain of eking out 5 extra years as the walking dead, before being sold for parts.

Final Thoughts

Leading a SaaS company is difficult, even in the best of times. These are not the best of times. But cost-cutting is not the ticket. We know that in SaaS if we are not growing we are dying. We must be able to make money on every sale and re-invest that profit in long-term, sustainable advantage.

When building the 2024 plan, most SaaS companies would benefit from a set of priorities like this:

Stop the bleeding. Get burn down to a level where your company can self-sustain for at least 2 years.

Fix your human-led GTM. Design, Activate and Operate a GTM Methodology that delivers acceptable unit economics (CAC Payback < 14 months).

Invest in your Product-led GTM. If you are paying people to execute any portion of your GTM that is automate-able, you are not only wasting money, you are handing competitive advantage to your rivals. The money you are spending on status quo they are investing in their future.

We can do this! These are just choices. A choice to hold on to how it was could be a choice to enter the land of zombies. But a choice to see where the future is headed and position your company to thrive in that environment may feel disruptive now and yet be ultimately company-saving in the long run.

We choose life.

XOXO,

-db

Loved it, Dave! Sounds familiar. Making me think very closely about our onboarding process in particular -- it's way too easy to casually lean on human-led motions that might be difficult to unwind.

Powerful advice that every Saas company needs to hear.